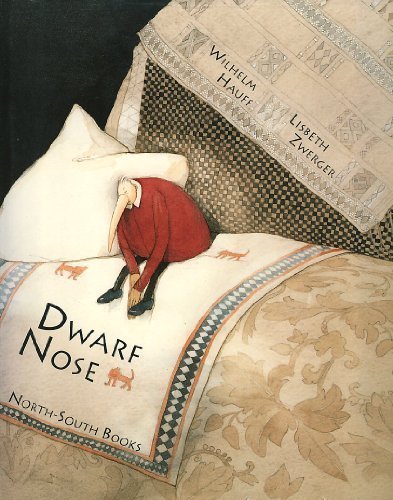

This morning, while reading Dwarf Nose, the German fairytale by Wilhelm Hauff and Lisbeth Zwerger, I was reminded of Karen Klein, the New York grandmother and bus monitor who was severely taunted by a group of boys on their way to school. Like everyone else who viewed the youtube video (one of the little creeps filmed the dreadful thing), I longed for retribution equivalent to the emotional abuse heaped on the poor woman, but how do you answer such shamefulness? In fairy tales, wickedness is punished, usually in some completely excessive and often spectacularly lethal way, which is not really appropriate (or possible) in the real world. Nevertheless, actions had consequences. In Dwarf Nose, a young boy, described as a ‘fine, handsome son, well built and quite tall for his age’, scolds an old crone for saying nasty things about his mother’s cabbages. Granted, she started it, but when the boy is cursed with the physical attributes he cruelly ridiculed in the old woman, I thought to myself, serves you right, ya little git.

However, I am certain 19th century delinquency is not the point of Dwarf Nose. Indeed, this unusually long tale by Wilhelm Hauff, a contemporary of the Brothers Grimm, is rather nuanced in spite of the mêlée at the vegetable stand. It is also the inspiration for a beautiful series of illustrations by the great Lisbeth Zwerger, who wields her own brand of enchantment, albeit across a modern and considerably less flinty land.

Typical of many fairy tales of the era, Dwarf Nose begins with a family of modest means whose suffering is made infinitely more acute by an unfortunate encounter with the supernatural. To help make ends meet, the cobbler’s wife sells fruits and vegetables at the town market, and her ‘handsome’ son Jacob encourages the local housewives and cooks to buy her wares, often carrying their purchases home for them. He is rewarded well for his efforts, returning to his mother with small coins, or pieces of cake. An old woman in tattered clothes approaches the stand, and proceeds to berate the quality of the herbs and vegetables on display. Wishing to defend his mother, the boy calls the woman a few choice names, casting aspersions on everything from her appearance to her overall filth. The crone ends up buying six cabbages, and upon his mother’s insistence, the boy carries the bags to her cottage. Let the weirdness begin…

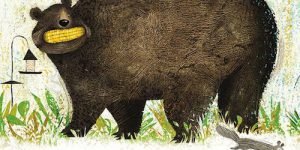

Though ‘tumbledown’ on the outside, the old lady’s house is a mansion within, serviced by guinea pigs dressed as human beings. After turning the cabbages into severed heads, the woman consoles the boy with a bowl of soup prepared by the guinea pigs. “There, child, there…just drink this soup and you’ll have everything you like so much about me.” Even more cryptically, she says, “And you’ll be a good cook too, so you’ll amount to something after all, but you’ll never find the herb.” Huh? The boy slips into slumber, and dreams that the old lady has wrapped him in the skin of a guinea pig. Strangely still, he dreams that he is taught a series of household chores, including the art of cooking. In fact, he is not dreaming at all and has been in the service of the old witch for seven years. When he returns to his mother, she does not know him, nor does his father. The boy has been turned into a dwarf, with a long pointy nose, a hunchback, spindly legs and spidery hands. But, as the old witch promised, he has an employable skill. That’s something.

Facing ridicule in town, Jacob finds work in the kitchen of the Duke, becoming Assistant Master Cook. Tragic  circumstances aside, the description and preparation of the food is quite wonderful. However, it’s not just the cooking; Dwarf Nose must also collect unusual foodstuffs for his recipes, including fat Geese for the Duke’s dinner. One goose in particular resists the pot, claiming that whomever tries to wring her neck will die. So, Dwarf Nose takes the goose home, and keeps her as his companion. When the Duke requests a meal of Sovereign Pie for his friend the Prince, the goose assists Dwarf Nose in finding the special herb required for the dish. Turns out, it is the same herb that the old lady used in the soup to enchant the boy. He packs his stuff, returns the goose to her father (who is able to remove the goosely curse), takes the herb, and transforms back into Jacob, the handsome cobbler’s son. End of story.

circumstances aside, the description and preparation of the food is quite wonderful. However, it’s not just the cooking; Dwarf Nose must also collect unusual foodstuffs for his recipes, including fat Geese for the Duke’s dinner. One goose in particular resists the pot, claiming that whomever tries to wring her neck will die. So, Dwarf Nose takes the goose home, and keeps her as his companion. When the Duke requests a meal of Sovereign Pie for his friend the Prince, the goose assists Dwarf Nose in finding the special herb required for the dish. Turns out, it is the same herb that the old lady used in the soup to enchant the boy. He packs his stuff, returns the goose to her father (who is able to remove the goosely curse), takes the herb, and transforms back into Jacob, the handsome cobbler’s son. End of story.

Well, sort of. Almost as an addendum to the tale, we learn that the disappearance of the dwarf creates strife within the Dukedom, erupting into the War of the Herbs. After many battles, it ends with the Peace of the Pie. As Wilhelm Hauff writes, “…small causes often have great (and sometimes delicious) consequences.” Yes. If only the kid had kept his mouth shut. On the other hand, everyone is decidedly better off after the conclusion of the fairy tale. And the grandmother in New York? She was able to retire with the charitable funds raised across North America following the incident on the bus. Happy endings are not just the stuff of fairy tales.

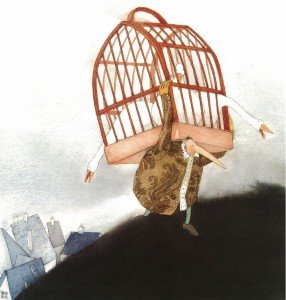

It goes without saying that Lisbeth Zwerger is the perfect illustrator for Dwarf Nose, and indeed any tale where strangeness intermingles with the supposed banality of everyday life. Guinea pigs in baggy Turkish trousers and green velvet caps do not seem out of place amongst the decorated bowls and pitchers of royal pantry. As with all of her books, the attention paid to the styles of clothing and other exquisite ‘background’ details are at least as beautiful as the character designs. The tiny figure of Dwarf Nose atop pillows and fabrics of overlapping patterns and colours is a breathtaking display of Zwerger’s artistic genius. Deftness with a watercolour brush is only part of it, however. In spite of his deformities, Dwarf Nose is far from repellant, but rather, vulnerable, and deserving of our compassion. Zwerger is brilliant at pulling heartstrings without ever resorting to sentimentality.

It goes without saying that Lisbeth Zwerger is the perfect illustrator for Dwarf Nose, and indeed any tale where strangeness intermingles with the supposed banality of everyday life. Guinea pigs in baggy Turkish trousers and green velvet caps do not seem out of place amongst the decorated bowls and pitchers of royal pantry. As with all of her books, the attention paid to the styles of clothing and other exquisite ‘background’ details are at least as beautiful as the character designs. The tiny figure of Dwarf Nose atop pillows and fabrics of overlapping patterns and colours is a breathtaking display of Zwerger’s artistic genius. Deftness with a watercolour brush is only part of it, however. In spite of his deformities, Dwarf Nose is far from repellant, but rather, vulnerable, and deserving of our compassion. Zwerger is brilliant at pulling heartstrings without ever resorting to sentimentality.

The art of Lisbeth Zwerger is awe-inspiring on every level, whether it’s the delicacy of her lines, the bold use of colour (refined over decades), the subtlety expressive faces of her characters (human, animal, or otherwise), the deep understanding of time and place, and above all, her wonderful grasp of the absurd. Lisbeth Zwerger, like Arthur Rackham before her, is the fairy tale interpreter of our generation.

In Lisbeth Zwerger: the World of Imagination, the catalogue from a recent retrospective at the Eric Carle Museum, Zwerger states that her Austrian childhood ‘posed no major problems.’ Her father was a graphic designer and painter, and her mother designed clothes for ‘beautifully costumed figures and dolls.’ No doubt, this was a rich, creative environment to develop as an artist, facilitated by her studies at the College of Applied Arts in Vienna. However, it was her relationship (and eventual marriage) to English illustrator John Rowe, and her introduction to publisher Friedrich Neugebauer, and his son Michael, that really got the ball rolling for Zwerger. In 1990, she received the Hans Christian Andersen Medal, the highest international award for lifetime achievement.

Wilhelm Hauff was born in Germany in 1802. By the time he died at the ripe old age of 25, he had amassed more than 30 volumes of his collected works.

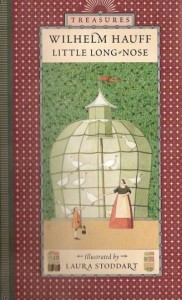

There are other interpretations of Dwarf Nose about, but of particular artistic merit is Little Long-Nose, with illustrations by Laura Stoddart. It’s quite lovely, and worth seeking out. It’s especially interesting to note the differences in translation. In Dwarf Nose, the herb used for the Duke’s breakfast is Bellyheal. In Little Long-Nose, it’s Stomach’s Consolation. And so on…

Dwarf Nose by Wilhelm Hauff (translated by Anthea Bell), illustrations by Lisbeth Zwerger. Published by North-South Books, 1994 (orig pub: Michael Neugebauer, 1993)

Lisbeth Zwerger: the World of Imagination, published by Michael Neugebauer, 2010

Little Long-Nose by Wilhelm Hauff, illustrated by Laura Stoddart. Published by Candlewick Press, 1997

Another Zwerger review ~ Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll