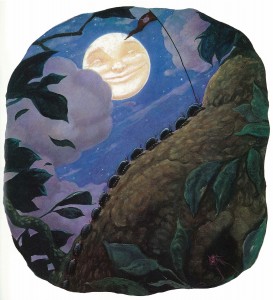

The Garden is a miraculous place, and anything can happen on a beautiful moonlit night.

The Garden is a miraculous place, and anything can happen on a beautiful moonlit night.

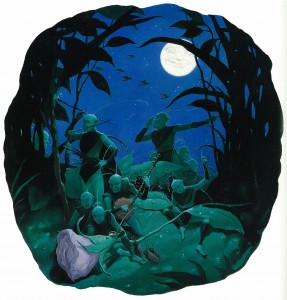

Yes. If summoned by the Brave Good Bugs, Leaf Men might swoop down from the trees, shoot a spider queen through the heart with an arrow made of thistle, save the life of an old lady and tend the garden. It could happen.

More importantly, you wish it could happen.

Most folks have a mental list of creative go-to’s: actors, writers, painters, chocolate manufacturers, etc., they will turn to over and over again for inspiration, stimulation, and pleasure. My list includes illustrators, and William Joyce has long been a charter member of this small group of artists who wander through the visual reference library in my brain, hanging and re-hanging paintings, tweeking the database, adding something new to the permanent collection every now and then.

The Leaf Men and the Brave Good Bugs is not new, but it’s quintessential Joyce: whimsical in the truest sense of the word, strange in any sense of the word, staggeringly gorgeous, narrative, and reverential. Joyce somehow manages to make his books feel cinematic, like old-timey movies, in particular screwball comedies and Errol Flynn adventures, with just a touch of sentimentality. This is especially true of A Day with Wilbur Robinson, another great Joyce picture book, but it is also present in The Leaf Men and the Brave Good Bugs. The only requirement is a comfortable chair and a big bowl of buttered popcorn.

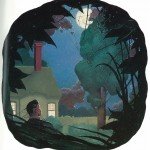

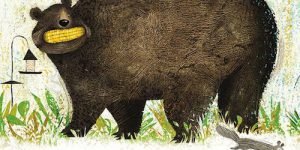

The story concerns a withered garden and a withered old lady, languishing in her bed, lost in dreams of the past. A ‘Long-Lost Toy’, hidden in the tall grass, made of metal and dressed in white tie and tails, advises the worried insects to call upon the legendary Leaf Men to save the garden, and the old lady. Leaf Men are ‘gardeners of a grand and elfin sort…who sew leaves back on, turn brown stalks green, and make the rosebush bloom like new.’ Sadly, as with all environmentally safe alternatives to garden chemicals, elfin fertilizers are notoriously hard to find. However, the Doodle Bugs, or Sowbugs with lips, bravely agree to take up the challenge, climbing to the highest point in the treetop to summon the Leaf Men.

Along the way, they encounter a very sinister looking

Spider Queen with a Jack Nicholson-like grin, intent on thwarting their quest by simply eating them for lunch. The Leaf Men, dashing in their Jolly Green Giant leotards, arrive and promptly slay the Spider Queen. Back in the garden, which the Leaf Men have revived, they inform the Metal Man that only he can can save the old lady, and so they carry him to the windowsill, along with a rose from the garden. She wakes up and is instantly filled with memories of her father, who had given her the toy to watch over her at night, and her mother, who had planted the rosebush to bring her comfort as a child. The old lady returns to her garden. And the Leaf Men return to William Joyce’s brain.

While the detailed and colour-saturated paintings in The Leaf Men and the Brave Good Bugs are reminiscent of N.C. Wyeth (without the heavy-handed grandeur), Joyce’s reverence for early 20th century aesthetics can be seen in the flourishes of art deco throughout the Leaf Men, and in many of his other publications. In spite of his prodigious skills as an artist and story-teller, William Joyce is essentially a big kid, and his watercolour illustrations have the playfulness and humour of a doodle. But a very, very good doodle. A doodle you would hang on the wall of a museum. In the autobiographical picture book, The World of William Joyce Scrapbook, it’s clear that Joyce has been a creative whirlwind from an early age. In the fourth grade, he wrote his first book entitled Billy’s Booger. According to his autobiography, he did not win first place, and was instead invited to ‘take a trip to the principal’s office.’ I have not seen this early Joyce production, but based on his track record thus far, I can state unequivocally that I would be proud to add Billy’s Booger to my collection. I just hope the principal had a sense of humour.

The Leaf Men and the Brave Good Bugs was inspired by a metal toy that Joyce purchased at an antiques store, which sat on his shelf until his daughter asked him to tell her a story while they were in the garden. He had a sick friend at the time, so somehow this wonderful story was born out of both truth and imagination. I suppose that could be said about most works of art, but there is only one William Joyce, and only he could have imagined such an elegant and offbeat story about an assortment of brave little bugs, a tin man in a tux, and a mythical race of gardeners known as the Leaf Men.

I would recommend the following video interviews from Reading Rockets, which you can view here. I think he speaks for all…or most artists when it comes to math, but only someone like Joyce would find whimsy in such misery.

The Leaf Men and the Brave Good Bugs by William Joyce, published by HarperCollins, 1996

The World of William Joyce Scrapbook, published by HarperCollins, 1994

A Day with Wilbur Robinson by William Joyce (to be reviewed), published by HarperCollins, 1990 (recently re-printed in hardcover by HarperCollins, 2006)

While you’re picking up these books, you might as well pick up the entire William Joyce library. You won’t be disappointed, and in fact, you will be permanently delighted…

Hi Donna, Just to let you know I’ll be linking to this post as part of a round up of reviews of books on the theme of elves and fairies, which will go live on Monday 14th May. 🙂

Yes, stretching theme a little, but such a lovely book I think it’s worth it.