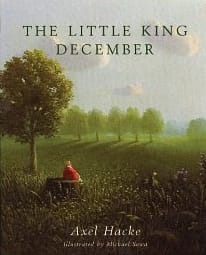

In this strange and beautiful book, an unnamed man relates the story of December II, the little pot-bellied king who visits the man from time to time, when the mood strikes. In King December’s world, you are big, and then you become small, and most curiously, you are born knowing everything you will ever know. As one would imagine in such a relationship, there are many things to ponder, on both sides, although surprisingly the presence of the miniature royal is never really questioned. “I’m only here because you wished it.” Well, maybe.

In this strange and beautiful book, an unnamed man relates the story of December II, the little pot-bellied king who visits the man from time to time, when the mood strikes. In King December’s world, you are big, and then you become small, and most curiously, you are born knowing everything you will ever know. As one would imagine in such a relationship, there are many things to ponder, on both sides, although surprisingly the presence of the miniature royal is never really questioned. “I’m only here because you wished it.” Well, maybe.

For many reasons, Little King December defies categorization. It is not a Christmas book exactly, but it belongs to the sugar plum month of December, from which the King’s own royal name derives, as sure as the ghost stories of Charles Dickens and Van Allsburg’s The Polar Express. The melancholic aching for things lost is the stuff of adulthood, but Little King December is distinctly childlike in its wide-eyed embrace of the whimsical and the wondrous. Familiar territory, in other words, for the absurdist German painter, Michael Sowa, the not so little King of Quirk.

“Will you tell me about your country?”

How does one answer that question? It’s cold, and it’s really, really large. What if the person asking lives in a tiny hole behind a bookcase, in a world that is entirely contrary to everything you know about the trajectory of existence? How do you answer then? What do you tell them about what it means to be human in your country? Thus begins the conversation in Little King December, an entirely original and thought-provoking book by German author, Axel Hacke. The story opens with the relationship between the man and the king already established. We never really know what precipitated these royal visits, or if indeed the visits are real, or imagined. It may in fact be a dream, and even the narrator is unsure whether or not he is the dreamer, or the dreamed. Sounds a bit ethereal but it’s not; the dialogue is as natural as a conversation overheard at a Starbucks, except rather than being across the table from one another~the participants converse mouth to pocket. Makes me think of those guys (it’s always guys) who walk around with a bluetooth connection, chatting affably, it seems, to no one.

While it’s clear the ever-curious King benefits from his friendship with the man, not least of which is a steady supply of Jelly Bears (his favourite food), it is the man who finds a kind of solace in the King’s descriptions of his world:

“You wake up, you lie there for a bit, you get up and you can write, do higher mathematics, write computer programs, you go to work and to business dinners. Only gradually you forget. The smaller you get, the more you forget. If someone can no longer participate in business dinners, it’s pointless got to the office: there’s no need for them there anymore. Then you have to stay home and you carry on forgetting more and more things. Your head becomes completely empty, with lots of room. Others have to cook for you, and afterwards you’re allowed to go and see your friends. Or watch shadows in the garden and pretend they’re ghosts. Or give names to clouds. Or torture your teddy bear…”

“He’s going to try to kill that poodle again.”

After a few pages, it becomes clear that the man needs the king. His life has become mundane, predictable. In their wanderings around town, King December lays fresh eyes on everything and everyone the man has long since become oblivious to, adding his own critical, and often wry insights. As they pass an old man walking his dog, the King says, ‘He’s going to try to kill that poodle again.” Say what?

The King then relates the story of the old man and his wife of 52 years, who he has grown to hate. “Oh, he’d much rather kill his wife, obviously, but he doesn’t dare.” In one attempt he ties the dog up at the Patent Office and leaves it there, but as luck would have it, someone had just patented a poodle-saving machine. So, the poodle is successfully rescued, inspiring yet another supremely loopy (but charming) illustration by Michael Sowa. On another walk, the King spots someone he knows is being stalked by a lovesick admirer. When the man asks why he just doesn’t move, the King replies, “Move? This is Munich. Just because you’re having a break with reality today, doesn’t mean you can forget the state of the property market!” Good advice, for those of us prone to the occasional mental vacation.

The juxtaposition of humour and pathos is present in both the text and in the art of Little King December. Perhaps it’s the shared German heritage, but this duality of perspective exemplifies the work of both the author and the illustrator. Also, a love-hate relationship with poodles. In other words, Axel Hacke and Michael Sowa are a damn near perfect match.

Little King December ends without any questions answered, just posed. What is the more desirable progression in life? The one that leads to imagination, or the one that leads to knowledge? Is it better to be born knowing everything you’ll ever know, with an understanding that the weight (and perhaps the drudgery) of life will slowly lift as you grow older? Or is it the familiar trajectory of acquired knowledge and experience, often at the expense of our innocence? Most importantly, are there really fire-breathing dragons down by the market square? We all long for the simplicity of childhood every now and again, but these things are not lost, they’re just buried. A book like Little King December serves to remind us in a most original, and funny, and lovely way, that life is odd. And remarkable. And maybe a little sad. And that sometimes…a slight twist to our perspective is all that is required to see the world anew, as if we were a child, or a little King.

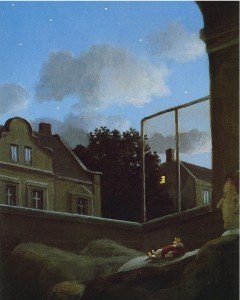

Michael Sowa was born in 1945 in Munich, Germany. I can’t think of another artist who possesses the painterly aesthetics of a great master, and the smart, empathetic,

and deadpan humour of a comedian. When I look at his art, I see Caspar David Friedrich in the dark landscapes of his backgrounds, and yet, he populates his paintings with miniature pigs, dragons, and poodle-catchers. As mentioned in a review of Esterhazy, I first came across Sowa’s incredibly imaginative artwork in a small card shop in Newcastle, 1993. And now, almost twenty years later, he is still one of my favourite artists, or the favourite, depending on the day. Sowa has a keen sense of how ridiculous and sublime it is to be human, and he extends these sensibilities to the creatures (real and imagined) that appear in his paintings in equal measure, including poodles.

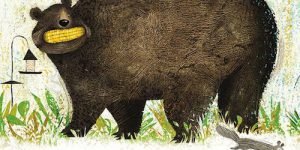

Unfortunately, I was not able to find a lot of information about Axel Hacke in English. He has a website, which appears to be quite engaging, but this is based entirely on visuals. I have no idea if the content is any good, but it’s gotta be, right? This guy is an amazing author, and I’m pleased to report that he collaborated with Michael Sowa on another book, A Bear Called Sunday, which may be reviewed in this blog at another time. Perhaps a Sunday in January or later in the spring. December belongs to a little pot-bellied King, and a man who can’t stop wondering if he was born the wrong way around.

Little King December by Axel Hacke, illustrations by Michael Sowa. Published by Bloomsbury, 2002

A Bear Called Sunday by Axel Hacke, illustrations by Michael Sowa. Published by Bloomsbury, 2003

Esterhazy: The Rabbit Prince–reviewed April, 2010 (Creative Editions, 1993), written by Irene Dische and Hans Magnus Enzensberger, illustrated by Michael Sowa