Marguerite’s Christmas isn’t for everyone.

The story of a fragile, elderly woman alone on Christmas Eve will leave some wondering if this is appropriate subject matter for children. Others will wonder if its appropriate subject matter for adults, given its juvenile format.

But it is a book for me, and anyone who sees storytelling as non-exclusionary. All stories have a place in children’s literature, as long as they are told well, told sensitively and honestly, and in the case of picture books, told with illustrative depth.

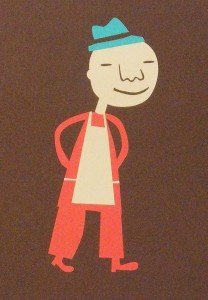

Marguerite’s Christmas is an extraordinary book. Written by Québecois author India Desjardins and illustrated by Pascal Blanchet (Trois-Rivières), Marguerite’s Christmas is one of the most beautiful books in recent memory, and it also deeply sad, because in Marguerite’s solitude we as readers want to reach out to her, even though her reality – being alone at Christmas – is not particularly unusual. The elderly are not always surrounded by family during the holidays like we see on TV, and some people, perhaps many people, are lonely at Christmas.

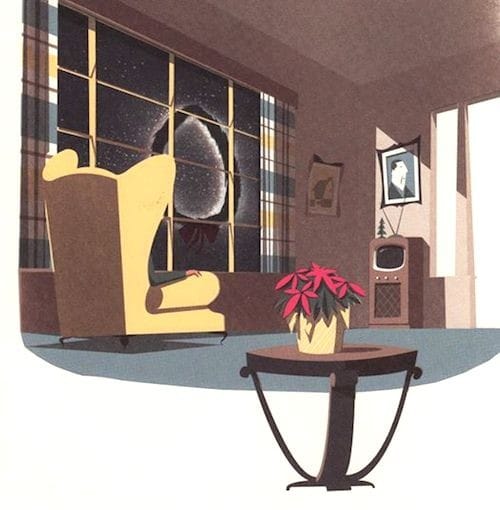

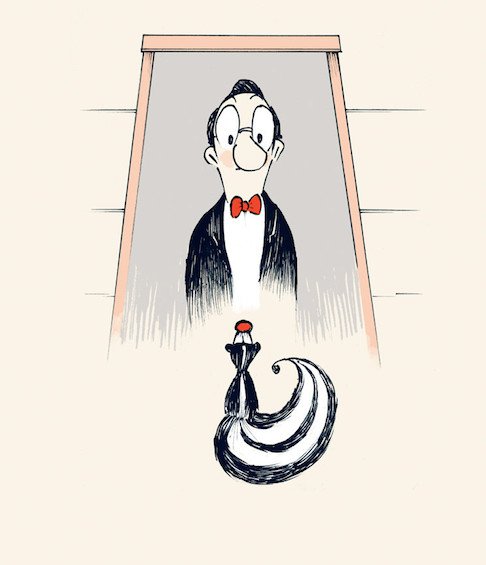

It’s difficult to know if I am ascribing feelings to Marguerite that she herself does not possess. She claims to be happy cocooning in her home, enjoying comforting rituals like watching her favourite holiday movies and not bothering with the tiresome fuss of Christmas. Many of her friends and family have died, and she is no longer interested in making new memories, just revisiting old. She repeatedly reassures her family that she is OK.

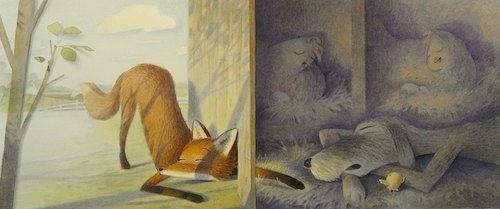

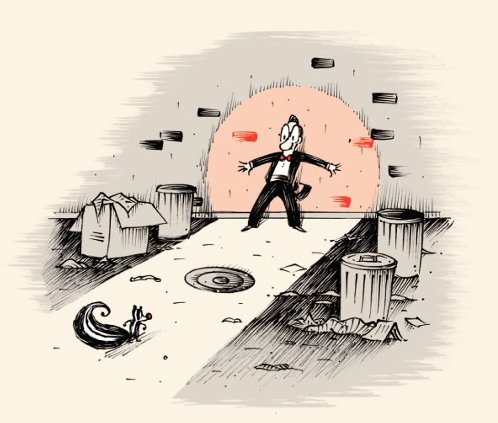

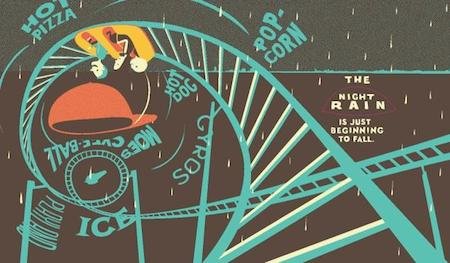

And yet, she is frequently startled by routine noises and fears going outside as if suffering from mild agoraphobia. She could probably use some company, but rejects it. Clearly, Marguerite is nearing the end, and at one point even imagines the grim reaper at her door. The scenes that follow give me pause. Is the episode with the car actually happening, or is it part of her ‘passage’ to the other side?

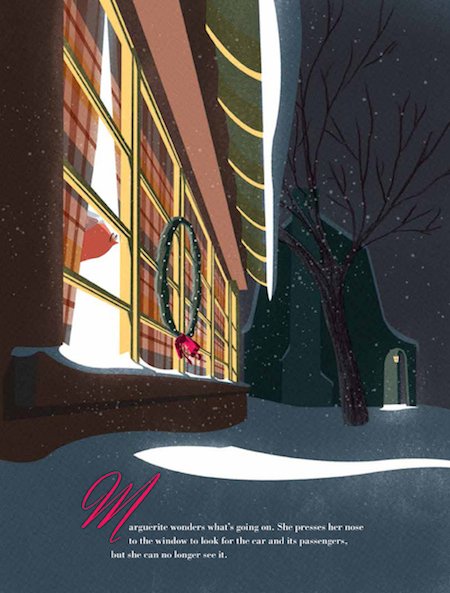

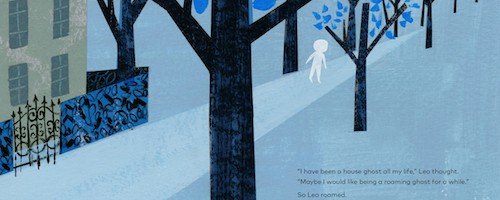

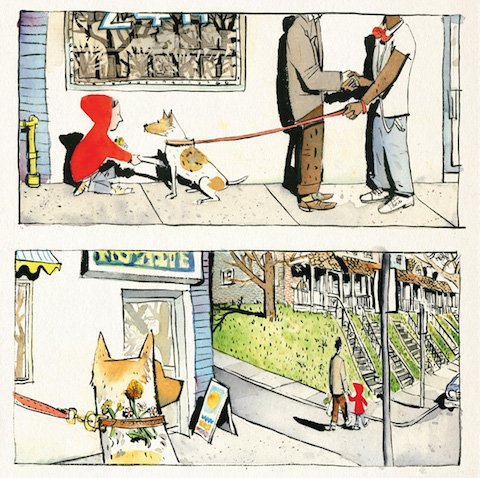

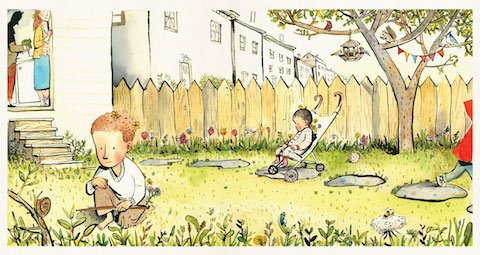

Unlike some adults (or this adult), children will take Marguerite at face-value. The story will not make them uneasy. Instead they will be engaged by Marguerite’s predicament, by her haplessness and vivid imagination (stunningly expressed by the illustrator). Marguerite is a real character. She is endearingly quirky and fastidious. In the most transcendent moment of the book, her kind heart triumphs over her natural reticence when, in spite of her apprehension about venturing outdoors, she helps a stranded family in a broken-down car. It has been a very long time since she has been outside, and the stillness and chill of the winter night releases her fear.

It’s a brave and respectful move by India Desjardins to tell this unvarnished story of an elderly person’s winding-down life, and pitch it at children. For everyone, life is a journey, and each moment has its inherent pleasures and torments. And even when you least expect it, a moment of wonder.

It’s a brave and respectful move by India Desjardins to tell this unvarnished story of an elderly person’s winding-down life, and pitch it at children. For everyone, life is a journey, and each moment has its inherent pleasures and torments. And even when you least expect it, a moment of wonder.

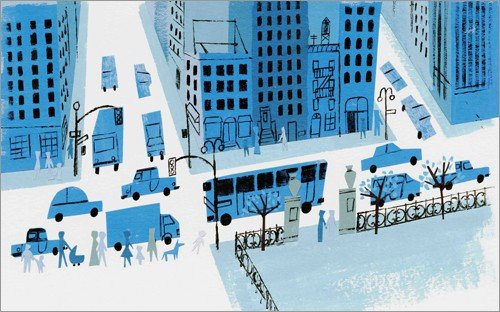

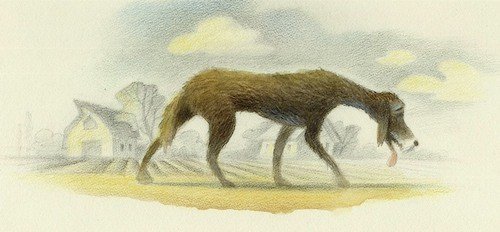

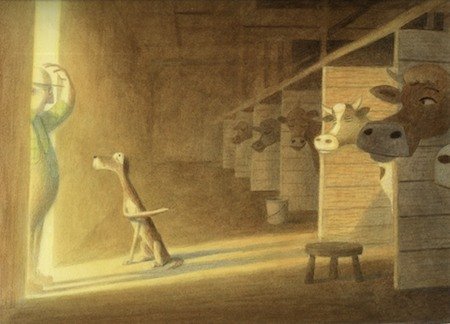

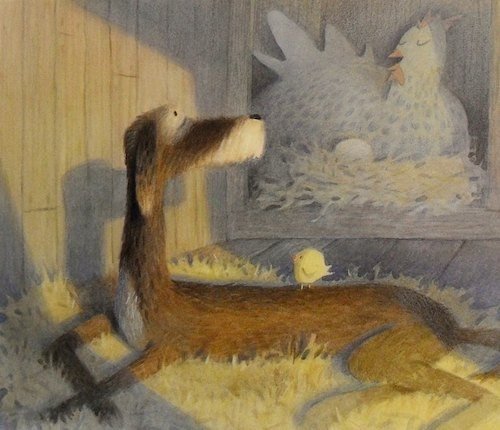

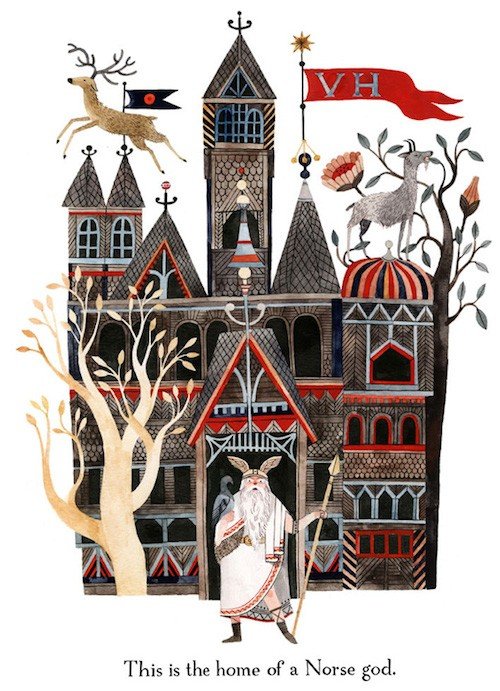

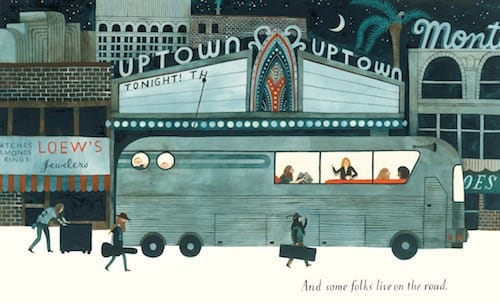

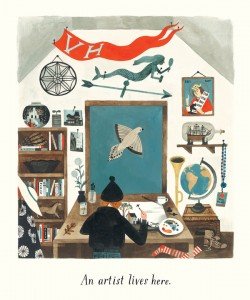

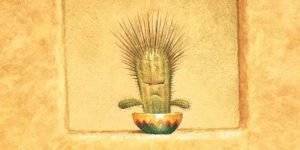

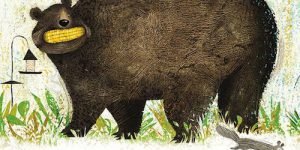

The illustrations by Québec illustrator Pascal Blanchet elevate Marguerite’s Christmas into classic holiday fare, pulling out and intensifying the humour and poignancy of Desjardins words. The art is simply stunning, full of quiet, snow-dolloped streets and retro-heavy vignettes that draw from Marguerite’s life, past and present. The exaggerated angles, stylized imagery and flat colours are very much in the manner of Eyvind Earle, one of Disney’s finest background artists. Several years ago, I bought a book of his Christmas card illustrations (800 in total). Blanchet’s winterscapes seem plucked from that magnificent collection of cards Earle created over 60 years ago.

Marguerite’s Christmas is perfection from the storytelling and illustration to the candy cane end-papers and placement of the type. It’s one of those books where everything works in exquisite balance, each element enhancing the expression of the other. Yes, it is at times an uneasy, layered read, but it is also deeply touching. I’ll not soon forget Marguerite. I feel like I’ve known her my whole life.

Marguerite’s Christmas by India Desjardins, illustrations by Pascal Blanchet. English edition, published by Enchanted Lion Books, 2015.

The original French edition of Marguerite’s Christmas, Le Noël de Marguerite (Les Éditions de la Pastèque, 2014) was shortlisted for the 2014 Governor General Literary Award in Canada for both text and illustration.

For more CHRISTMAS PICTURE BOOK REVIEWS, click HERE. Within that post, is a link to an even longer list of Christmas books!