Unease. Disquiet. Anxiety. Not the usual payoffs you find in children’s picture books, unless the author’s name is Grimm. Or Sendak.

Outside Over There is the third of Maurice Sendak’s self-described trilogy, which includes Where the Wild Things Are and In the Night Kitchen. Stylistically, I see no similarity, but according to Sendak, “They are all variations on the same theme: how children master various feelings – danger, boredom, fear, frustration, jealousy – and manage to come to grips with the realities of their lives.” Uh oh. Are these things supposed to go away with the onset of adulthood? Some of us retain a level of unease with the world that is mirrored and acknowledged in books like Outside Over There. Is that bad?

In this simple but deeply nuanced story, a young girl named Ida wrestles with feelings of ambivalence towards her baby sister, upon whose safekeeping she has been entrusted. The father is away at sea, and Ida’s mother is oblivious to everything but her own suffering. As Ida plays her wonderhorn, the baby is snatched by goblins, replacing it with a changeling made of ice. Being the baby sister in my family, I think this would have been a welcome turn of events. However, Ida is horrified when the ice baby starts to melt, and vows to rescue her sister. Compounding her predicament, Ida makes a ‘serious mistake’ by climbing backwards out her window into outside over there, landing smack in the middle of a goblin wedding where the bride is Ida’s sister, and the five grooms are all babies. Goblin babies. The good news is that goblins appear to be strangely sensitive to music, and Ida is able to ‘churn them into a dancing stream’ with her wonderhorn, leaving her baby sister unharmed. Ida returns to her mother, who fails recognize the trauma that her two daughters have just endured, and instead, waves a note from her husband saying that until he returns, Ida must continue to watch over her sister and her mother. Done and done. Now I know how my oldest sister felt.

The unpredictability of life, and the dangers that await us from within our homes and especially from without are themes that arise from Sendak’s own history. Most of his family were murdered in Nazi concentration camps, and Sendak infuses this book, and others, with a sobriety rarely seen in children’s picture books.

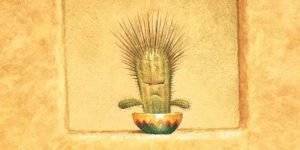

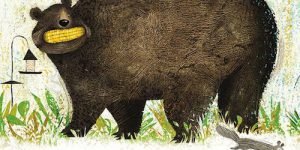

The illustrations in Outside Over There reference a variety of artistic styles, especially the German Romanticists, and in particular, the work of Caspar David Friedrich (settings) and Otto Runge (babies.) Good artists borrow, great artist steal, as someone once said, and in the depiction of Ida’s sister, it’s clear that Sendak was heavily influenced by Runge’s drawings of

infants. However, the most distinctive element in Sendak’s illustrations in this book, and also his later publication, Dear Mili, is the unique way he distorts perspective, in particular the physicality of children. They all have big heads and huge, adult feet, as if they have been compressed. It’s very compelling, and strangely beautiful. In Outside Over There, even the frame of the picture is compressed, metaphorically squeezing Ida into a claustrophobic existence, with responsibilities and concerns beyond her young age.

The watercolour paintings are much softer than the pen & ink illustrations in Where the Wild Things Are or the bold, graphic style of In the Night Kitchen, but don’t be fooled. The apparent mildness of Outside Over There exists only in the application of the paint, not in the text or the content of the illustrations. Once the goblins appear at the window, the benign domestic setting morphs into something ominous. The sunflowers claw through the window in increasing quantity. Through the shutters, the scene changes from trees, to a ship, to a shipwreck, and finally to a broiling Turneresque sea. There is no stability in Ida’s world, and  it is quite clear she is on her own.

it is quite clear she is on her own.

Browsing through the internet, I found many interpretations of Outside Over There, including possible sexual overtones (you’d think if this were true it would be called Inside Over Here), which is indicative of a writer and illustrator bringing more to the table than just a pretty picture book. There is a definite corollary with Grimm in Outside Over There in the sombre treatment of childhood, and the belief that the emotional lives of children are far more complex than widely assumed. In any case, Outside Over There is a story that stays with you. It has the resonance and strangeness of an old fairy tale, even though it’s a mere 29 years old.

Outside Over There by Maurice Sendak, published by HarperCollins, 1981

Dear Mili by Wilhelm Grimm (to be reviewed), published by HarperCollins, 1988

The Art of Maurice Sendak by Selma Lanes, published by Harry N Abrams, 1980

The Romantic Child: From Runge to Sendak by Robert Rosenblum, published by Thames & Hudson, 1988