Of all the days in the year in Canada that we celebrate or commemorate, Remembrance Day is the one that means the most to me. Other seasonal occasions, like Christmas, hold fond places in my heart, filled as they are with memories of friends and family, and my unnatural love of winter, twinkle lights, and all the Who’s down in Whoville.

Remembrance Day, on the other hand, engages me emotionally and spiritually like no other day of the calendar. No cards or presents are exchanged, no fireworks, no hollowed-out pumpkins. It is the one day set aside for quiet reflection, not on our lives but the lives of others who participated in the wars of the 20th century and beyond, who even now are buried in fields where poppies blow. I have no direct experience with war, other than through my brother-in-law whose mother was taken from her Polish village and brought to Germany as a labourer, and his father, who fought with the exiled Polish army all over Europe and the Middle East. I am not a war nut; the specificities of battles and campaigns do not interest me, but I do wonder why people do the things they do. How decisions, large and small, play out through time.

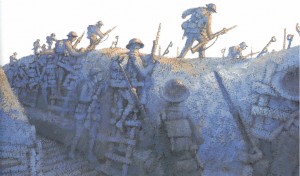

Like many armchair ‘historians’, and I use that term extremely loosely, I have watched movies and read many books, usually novels but also biographies and the occasional historical text (if it favours narrative over battle strategy.) Among the best is A Brave Soldier, a children’s picture book about WWI by Nicolas Debon. In this quiet gem of a story, a young man named Frank and his friend Michael enlist in the army when they learn that Canada is at war. It is 1914, and they believe they’ll be home by Christmas. Frank spends the first six months in England training to be a soldier, and is then sent to France where he and his companions are guided through a maze of ditches to a trench running parallel to a ruined field called No Man’s Land. And they wait, in the mud and rain.

Like many armchair ‘historians’, and I use that term extremely loosely, I have watched movies and read many books, usually novels but also biographies and the occasional historical text (if it favours narrative over battle strategy.) Among the best is A Brave Soldier, a children’s picture book about WWI by Nicolas Debon. In this quiet gem of a story, a young man named Frank and his friend Michael enlist in the army when they learn that Canada is at war. It is 1914, and they believe they’ll be home by Christmas. Frank spends the first six months in England training to be a soldier, and is then sent to France where he and his companions are guided through a maze of ditches to a trench running parallel to a ruined field called No Man’s Land. And they wait, in the mud and rain.

To pass the time, Frank plays cards, writes letters to his parents, picks lice out of his hair and clothes, awaits the orders that will send him ‘over the top.’ He thinks about the Germans on the other side of No Man’s Land, listens to their voices, wonders if they too have families waiting for them in Germany. It is a moment of stillness before all hell breaks loose, literally. Frank wakes up in a blast hole in the ground, remembers the deafening noise and watching a man next to him fall, but nothing else. He is still recovering on November 11th when he learns the war is over. Frank visits the grave of his friend Michael, buried in a military cemetery, before taking the ship home to Canada.

A Brave Soldier is sombre story both in tone and in subject matter, as befits one of the saddest events of the 20th century, but there is something beautiful in the manner in which Nicolas Debon is able to distill war, in this case WWI, into the very essence of what it means to be a soldier: patriotism, duty, exhilaration, boredom, suffering, confusion, and fear. My guess is that it was no accident that the book is called A Brave Soldier…not The Brave Soldier. Frank’s experience is not unique, and the term ‘brave’ could be applied to Frank, or Michael, or any of his comrades in arms. In a palette drenched in earthtones and mud, Debon captures small-town Canada and the sodden, crater-filled fields of France with an Impressionist’s brush. Casting shadows of blue, purple and gold along the mud walls of the trenches and in the stricken faces of the soldiers lining up for battle, the pictures have a kind of terrible beauty, elevating what could have been a very dreary series of war ‘snapshots’ to illustrations of heart-wrenching poignancy.

century, but there is something beautiful in the manner in which Nicolas Debon is able to distill war, in this case WWI, into the very essence of what it means to be a soldier: patriotism, duty, exhilaration, boredom, suffering, confusion, and fear. My guess is that it was no accident that the book is called A Brave Soldier…not The Brave Soldier. Frank’s experience is not unique, and the term ‘brave’ could be applied to Frank, or Michael, or any of his comrades in arms. In a palette drenched in earthtones and mud, Debon captures small-town Canada and the sodden, crater-filled fields of France with an Impressionist’s brush. Casting shadows of blue, purple and gold along the mud walls of the trenches and in the stricken faces of the soldiers lining up for battle, the pictures have a kind of terrible beauty, elevating what could have been a very dreary series of war ‘snapshots’ to illustrations of heart-wrenching poignancy.

As I was writing this review, I came across a file at work that had previously garnered no special attention until an email from a doctoral student in Toronto compelled me to look past the first few pages in search of contact information for a man in whose name a scholarship had been endowed. The man was Mr John Proskie, agricultural economist and, as I later found out, a member of the RCAF during WWII. After flipping through to the back of the file, I came across biographical information that astounded me: Squadron Leader Proskie, from Edmonton, Alberta, assisted by only one British sergeant and trucks supplied by the British army and the RAF, fed more than 61,000 starving Polish, Hungarian, French, Russian and German victims from Bergen-Belsen concentration camp during the first few days of the camp’s liberation, and beyond. When Proskie arrived on April 17th, he faced a humanitarian crisis of unimaginable scale. Proskie used his agricultural expertise, natural pragmatism, and a serious case of chutzpah to procure food for a small city of emaciated souls. In one week, he and his team had gathered 40,000 pounds of fresh meat, 68,000 pounds of onions, 1000 pounds of strawberries and 13,000 pounds of rhubarb. Farmers were visited, food reconnaissances made, the RAF and British Second Army went on short rations both for food and luxuries like soap and cigarettes to allow the camp to be supplied*, and according to Proskie’s brother, when faced with obstacles “he just went out into the countryside and commandeered food from the Germans.”** The death rate dropped from 500 daily at the end of April to 20-40 in June. Up until a few days ago, I had never heard of this man, at least in relation to his ‘other’ life as a soldier.

Following Proskie’s honourable discharge from the RCAF in 1946, the British Foreign Office assigned him the task of procuring and distributing food during the Berlin Airlift. He died in 1993 at the age of 87.

John Proskie was some soldier. A brave soldier, and by all accounts, a very modest man who did a very big thing a long time ago. On November 11th, I will remember him.

Nicolas Debon was born in Northern France and later moved to Nancy where he studied art at l’École nationale des Beaux-Arts. His work with the visual arts branch of the Ministry of Culture in France led him to a position at the French consulate in Toronto, where he lived and eventually worked as an illustrator for ten years. Mr Debon recently moved back to France.

A Brave Soldier by Nicolas Debon, published by Groundwood Books, 1993. Unfortunately, this book is currently out of print, but absolutely worth seeking out.

Thank you to Mark Celinscak, a PhD student at York University (now professor at Trent U) for sending me that email. His book Distance from the Belsen Heap: Allied Forces and the Liberation of a Nazi Concentration Camp (University of Toronto Press, 2015), is now available.

November 5th, 2012~Addendum to this post. In February, 2012 Mr Walter Adamowicz passed away at the age of 96. He served in the Polish Second Corps as a member of the 5th DKP, 16th LBS. I respectfully dedicate this post to Mr Adamowicz~WWII soldier~outstanding storyteller.

A few other recommendations: a book that literally changed how I feel about Remembrance Day…Birdsong by Sebastian Faulks. A great novel, and one of the most moving stories of WWI I’ve ever read. Also, Joyeux Noel, a superb film about WWI, and in particular the Christmas Eve ‘truce.’

Read my thing about Thing-Thing, illustrated by Nicolas Debon.

*Toronto Daily Star July 18, 1945

**Edmonton Journal September 9, 1993