Well, OK then. The fact that the child is not wearing a red hood already differentiates one story from the other. And there’s the bear. Not a wolf, mind you, but a big, white bear. As the rosy-cheeked girl in Alessandra Lecis and Linda Wolfsgruber’s new book I Am Not Little Red Riding Hood is so keen to remind us, her story has nothing to do with the Grimm (or Perrault, depending on the translation) fairy tale. Yes, she has a red scarf, and she takes a basket into the woods, but that is the end of it. This is her story.

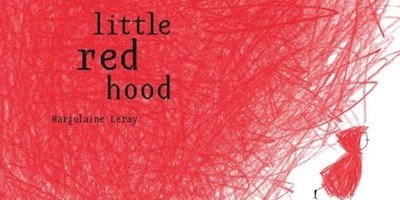

Little Red Hood

Sometimes magnificent little confections appear before me in bookshops. I am powerless to resist, and really, I have no interest in resistance, as my teetering bookshelves can attest. If it’s good, I’ll buy it. Little Red Hood by Marjolaine Leray is such a book. Modest in size and colour (red, white, black), it is the very embodiment of simplicity, and yet Little Red Hood packs a punch in several unexpected ways.

The story of the red-hooded waif and the trickster wolf with the insatiable appetite for little girls and grannies is a familiar one, although the resolution varies greatly between the various translations. In the Perreault version, the grandmother outwits the wolf. In Grimm’s Little Red Cap, the wolf is split open by the huntsman. In Bugs Bunny, Little Red Riding Hood is so obnoxious, Bugs and the wolf conspire to end their misery. And so on. Very rarely does the wolf triumph, but then, neither does the girl, other than having her life spared. She is always (with the exception of Bugs) rescued. In Little Red Hood, the girl is her own hero, outwitting the wolf, thus saving her self from his exceptionally long and toothy snout. Commenting on his bad breath, the girl offers the wolf a sweet, but not just any sweet. Suffice to say, there is no end to this girls’ resourcefulness.

The story of the red-hooded waif and the trickster wolf with the insatiable appetite for little girls and grannies is a familiar one, although the resolution varies greatly between the various translations. In the Perreault version, the grandmother outwits the wolf. In Grimm’s Little Red Cap, the wolf is split open by the huntsman. In Bugs Bunny, Little Red Riding Hood is so obnoxious, Bugs and the wolf conspire to end their misery. And so on. Very rarely does the wolf triumph, but then, neither does the girl, other than having her life spared. She is always (with the exception of Bugs) rescued. In Little Red Hood, the girl is her own hero, outwitting the wolf, thus saving her self from his exceptionally long and toothy snout. Commenting on his bad breath, the girl offers the wolf a sweet, but not just any sweet. Suffice to say, there is no end to this girls’ resourcefulness.

A Fairy Tale of Poland

The beauty of writing a blog with a focus on illustration is that I can downplay the story if it’s unremarkable, or if, as with the case of Od Baśni do Baśni (From Story to Story), it is so remarkable that it is beyond comprehension. Not that Polish is particularly remarkable, but it is beyond comprehension, especially for those of us who are not familiar with the language, and/or have a fondness for vowels.

The book was unearthed in the basement of the parents of my brother in law. Sadly, they passed away this last  year, and now their children are sifting through the remnants of their long lives. No one remembers this book, or how it came to be in their possession. Published in 1965, it’s certainly of the era of my brother in law’s childhood, but the provenance is uncertain. Nevertheless, it is now in my hands, if temporarily, and I couldn’t be more tickled.

year, and now their children are sifting through the remnants of their long lives. No one remembers this book, or how it came to be in their possession. Published in 1965, it’s certainly of the era of my brother in law’s childhood, but the provenance is uncertain. Nevertheless, it is now in my hands, if temporarily, and I couldn’t be more tickled.

Although not familiar with Jan Marcin Szancer, the illustrator of od Baśni do Baśni, his style (at least in this particular outing) is straight out of the sixties. The unusually vibrant colour plates may be a result of the era’s pre-separation printing process, but regardless of how the images made it to the page, Szancer’s illustrations (in colour and black & white) bare a striking similarity to the work of his compatriots outside of Poland. Certainly, Szancer’s humourous and delightfully jaunty approach to illustration is not unlike Ronald Searle or even Paul Galdone, which makes the stories even more tantalizing. Something funny is going on here, but what?

Although not familiar with Jan Marcin Szancer, the illustrator of od Baśni do Baśni, his style (at least in this particular outing) is straight out of the sixties. The unusually vibrant colour plates may be a result of the era’s pre-separation printing process, but regardless of how the images made it to the page, Szancer’s illustrations (in colour and black & white) bare a striking similarity to the work of his compatriots outside of Poland. Certainly, Szancer’s humourous and delightfully jaunty approach to illustration is not unlike Ronald Searle or even Paul Galdone, which makes the stories even more tantalizing. Something funny is going on here, but what?

Dwarf Nose

This morning, while reading Dwarf Nose, the German fairytale by Wilhelm Hauff and Lisbeth Zwerger, I was reminded of Karen Klein, the New York grandmother and bus monitor who was severely taunted by a group of boys on their way to school. Like everyone else who viewed the youtube video (one of the little creeps filmed the dreadful thing), I longed for retribution equivalent to the emotional abuse heaped on the poor woman, but how do you answer such shamefulness? In fairy tales, wickedness is punished, usually in some completely excessive and often spectacularly lethal way, which is not really appropriate (or possible) in the real world. Nevertheless, actions had consequences. In Dwarf Nose, a young boy, described as a ‘fine, handsome son, well built and quite tall for his age’, scolds an old crone for saying nasty things about his mother’s cabbages. Granted, she started it, but when the boy is cursed with the physical attributes he cruelly ridiculed in the old woman, I thought to myself, serves you right, ya little git.

However, I am certain 19th century delinquency is not the point of Dwarf Nose. Indeed, this unusually long tale by Wilhelm Hauff, a contemporary of the Brothers Grimm, is rather nuanced in spite of the mêlée at the vegetable stand. It is also the inspiration for a beautiful series of illustrations by the great Lisbeth Zwerger, who wields her own brand of enchantment, albeit across a modern and considerably less flinty land.

Typical of many fairy tales of the era, Dwarf Nose begins with a family of modest means whose suffering is made infinitely more acute by an unfortunate encounter with the supernatural. To help make ends meet, the cobbler’s wife sells fruits and vegetables at the town market, and her ‘handsome’ son Jacob encourages the local housewives and cooks to buy her wares, often carrying their purchases home for them. He is rewarded well for his efforts, returning to his mother with small coins, or pieces of cake. An old woman in tattered clothes approaches the stand, and proceeds to berate the quality of the herbs and vegetables on display. Wishing to defend his mother, the boy calls the woman a few choice names, casting aspersions on everything from her appearance to her overall filth. The crone ends up buying six cabbages, and upon his mother’s insistence, the boy carries the bags to her cottage. Let the weirdness begin…