In my world, a new publication from Lisbeth Zwerger is an event. At the risk of veering into hyperbole, she is the Arthur Rackham of her generation and will be remembered well beyond her time on earth. Zwerger’s latest is Tales From the Brothers Grimm, a collection of previously published stories and a few new yarns, including The Frog King or Iron Henry, The Brave Little Tailor, Briar Rose, The Poor Millers’ Boy and the Little Cat, and Hans My Hedgehog. The stories chosen by Lisbeth Zwerger to illustrate and include in this book speak to her quirky sensibilities and unparalleled talent for visual storytelling. From beginning to end, Tales From the Brothers Grimm is an impressive and extraordinarily beautiful overview of an astonishing career.

Although Lisbeth Zwerger has a recognizable style, her work continues to evolve. Early in her career, she favoured the sepias and high contrast hues of her predecessors, in particular the aforementioned Arthur Rackham with whom she “…landed in a Rackham-vortex.”* His influence can be seen in Hansel and Gretel and The Seven Ravens, which are included in Tales From the Brothers Grimm. Although these stories and others from this period are lovely and possess  the seeds of what was to come, they fall within the continuum of classic children’s illustration, rarely transcending it. As her colours brightened, so did her playfulness. The true genius of Lisbeth Zwerger emerged alongside a deeper, richer palette fully integrated with a wit and visual complexity well suited to the peculiar world and work of the Brothers Grimm.

the seeds of what was to come, they fall within the continuum of classic children’s illustration, rarely transcending it. As her colours brightened, so did her playfulness. The true genius of Lisbeth Zwerger emerged alongside a deeper, richer palette fully integrated with a wit and visual complexity well suited to the peculiar world and work of the Brothers Grimm.

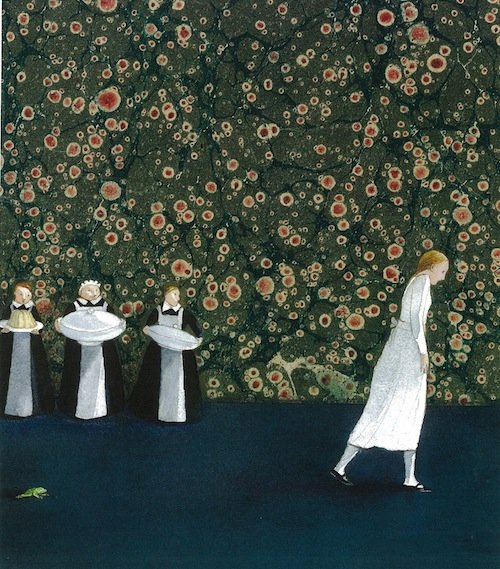

One of the best examples of Zwerger’s mature style is The Frog King or Iron Henry. In the first illustration, the King’s youngest daughter moves swiftly down a hedgerow in an attempt to outrun the amorous frog. The hedge appears to be a slice of plant tissue as viewed from under a microscope. Beautiful of course, but unusual and strikingly inventive. Who would have thought to do this but her? The frog is persistent, and when he asks to join the young lady in bed (‘I want to sleep in as much comfort as you’), she responds by throwing him against the wall, where he turns into a handsome prince. If only it were that easy.

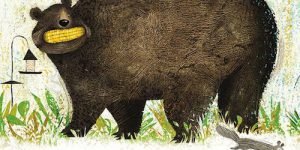

The Wolf and the Seven Young Kids is Grimm in origin and in nature. A wolf tricks a nanny-goat’s ‘kids’ into letting him in the door, where he promptly eats six of them. Mama Nanny-Goat returns, and the youngest kid points to the wolf, sleeping off his food coma on a nearby hill. When she sees something ‘wriggling inside his big, over-stretched belly’, she sends the seventh kid to fetch a pair of scissors, a needle, and some thread. Minutes later, the kids are out, replaced with rocks, and the wolf has a large incision on his belly. The fact that he does not wake during surgery suggests a deft hand on the part of Ms Goat. Later, when the wolf leans over for a drink of water, the weight of the stones drags him down into the well where he ‘drowns miserably.’ (Frankly, I can think of no other way to drown.) Zwerger’s light-hearted illustration of the bloated, sleeping wolf is an amusing distraction from the abject violence so typical of a Grimm fairytale.

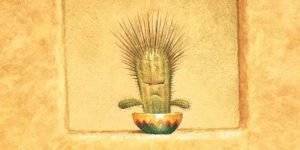

In Hans My Hedgehog, definitely one of the stranger tales in the collection, a childless couple wishes for a boy, ‘even if it were to be a hedgehog!’ Fate, in life and especially in fairytales, has a wicked sense of humour. The wife gives birth to a child  who is hedgehog above the waist, and a boy below. They are not pleased, but begrudgingly agree to baptize him Hans My Hedgehog. The poor thing is banished to a straw bed behind the stove. In my favourite illustration in the book, the wife has just given birth (I don’t even want to think about it), and her spiny child is asleep on the bed. Hans My Hedgehog is curled up on his side, naked from the waist down, his little bum exposed to the air. The husband, unaware that his wife has given birth to a hedgehog, stands just behind the curtain with a bouquet of flowers. The wife’s apprehension, the husband’s joy, and the utter vulnerability of the tiny hedgehog is beautifully captured in Zwerger’s deeply empathetic painting. The bed is draped by a curtain made of coloured striations, like ribbon candy softened and pulled into a sheet. Unfortunately, my scanner is no match for Zwerger’s delicate watercolours, hence the poor reproduction, but the entire illustration is exquisite.

who is hedgehog above the waist, and a boy below. They are not pleased, but begrudgingly agree to baptize him Hans My Hedgehog. The poor thing is banished to a straw bed behind the stove. In my favourite illustration in the book, the wife has just given birth (I don’t even want to think about it), and her spiny child is asleep on the bed. Hans My Hedgehog is curled up on his side, naked from the waist down, his little bum exposed to the air. The husband, unaware that his wife has given birth to a hedgehog, stands just behind the curtain with a bouquet of flowers. The wife’s apprehension, the husband’s joy, and the utter vulnerability of the tiny hedgehog is beautifully captured in Zwerger’s deeply empathetic painting. The bed is draped by a curtain made of coloured striations, like ribbon candy softened and pulled into a sheet. Unfortunately, my scanner is no match for Zwerger’s delicate watercolours, hence the poor reproduction, but the entire illustration is exquisite.

As he grows, Hans My Hedgehog makes few demands on his parents, requesting only a set of bagpipes from the local market and shoes for his rooster. With that, he rides off to the woods on his newly shod rooster to herd pigs and donkeys, promising his father never to return. Hans My Hedgehog learns to play the pipes beautifully, and his animals prosper. After several acts of kindness to various royalty who pass his way, Hans My Hedgehog ends up with a King’s daughter, and the spell is broken.  Interestingly, although Hans My Hedgehog outwits the King, he is never mean or vengeful in spite of the cruelty visited upon him by his parents and the first King. I’ve read other versions of the tale where Hans My Hedgehog isn’t quite so generous of spirit, but this translation by Anthea Bell brings a lyricism to the story, just as Zwerger’s poignant illustrations deepen the emotional impact of the words.

Interestingly, although Hans My Hedgehog outwits the King, he is never mean or vengeful in spite of the cruelty visited upon him by his parents and the first King. I’ve read other versions of the tale where Hans My Hedgehog isn’t quite so generous of spirit, but this translation by Anthea Bell brings a lyricism to the story, just as Zwerger’s poignant illustrations deepen the emotional impact of the words.

The Tales of the Brothers Grimm is a gem of the finest cut.

Lisbeth Zwerger was born in Vienna in 1954. She has won numerous awards for her work, including the prestigious Hans Christian Andersen Medal, presented to her in 1990 to recognize her lifetime contribution to children’s literature.

Tales From the Brothers Grimm, selected and illustrated by Lisbeth Zwerger. Translation by Anthea Bell. Published by Minedition, 2012

Tales From the Brothers Grimm, selected and illustrated by Lisbeth Zwerger. Translation by Anthea Bell. Published by Minedition, 2012

Dwarf Nose by Wilhelm Hauff (translated by Anthea Bell), illustrations by Lisbeth Zwerger. Published by North-South Books, 1994 (orig pub: Michael Neugebauer, 1993)

Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll, with illustrations by Lisbeth Zwerger. North-South Books, 1999

*Lisbeth Zwerger: the World of Imagination, published by Michael Neugebauer/Minedition, 2010

Agreed, Lisbeth is divine and a constant source of inspiration for my own drawing.

Oh my goodness!! I’m so excited for this 🙂 When does it come out?? I’ve been away from blogging for a little over a month due to school and I feel so out of the loop haha. I’m working on my final right now choosing 5 illustrations for Brothers Grimm tales that highlight elements of the fairy tale as a genre…I think I’m going to use a few from Lisbeth Zwerger, and I agree with you, I think she may very well be the Arthur Rackham of our time!!

Hi Jess,

I’m not sure when it will be released in North America. I was trolling the Minedition website, her publisher, and came across this book, and other wonderful books by other illustrators, including a few that have not yet been translated into English (from German.) So…over to Amazon.uk because I didn’t see any of them on Amazon Canada, or US. It’s worth the wait (and the expense)though…

Have fun at school!

Donna

Dear Donna,

thank you so much for this phantastic review!!!!

I feel so flattered.

As far as I know my minedition books are available

in English (try Amazon).

Arthur Rackham was my absolute hero for many years

and definitely the illustrator who started me off.

I would have never ever dreamt of receiving the title

“Arthur Rackham of my generation” – I nearly fainted when

I first read it.

Thanks again

and all the best

Lisbeth

Well, I can die now.

Thank you Lisbeth.

I was collecting all Lisbeth’ books when my daughter was young.

I suddenly remembered how much I missed her illustrations and found this!

I cried.

Thank you sooo much, love it!!!!!