There has been a lot of discussion in the news of late regarding the pervasiveness of dystopian young adult literature, and whether or not it’s appropriate to expose kids to the darker aspects of life, real or imagined. I think we are kidding ourselves if we believe that children and young adults exist in bubbles, and are not in some way already exposed to the full spectrum of humanity.*

When I was a young girl, maybe 13 or 14, I abandoned what was ‘appropriate’ for my age and fell headfirst into the novels of Stephen King, Kurt Vonnegut and even Margaret Laurence because what I was reading did not reflect the unpredictability and to a degree, the harshness of my life at that time. Nevertheless, most of us in Canada and elsewhere in the developed world lead a comparatively pampered life. Some more pampered than others, but the bulk of us grow up with a roof over our heads, food in our bellies, and if we’re lucky, a sense of permanency, all of which is taken for granted because it is the rule, not the exception. Migrant is the story of a girl who lives the exception, but in the most poetic way, brings a beauty to the unpredictable life around her and to the world she imagines for herself and her family.

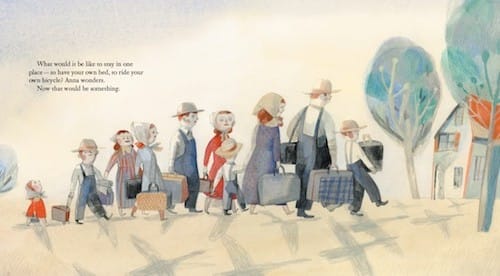

Anna is the youngest child of a Mennonite family that has long since emigrated to Mexico, traveling back to Canada every summer to pick fruit and vegetables. She pictures her family as a flock of geese, chasing the sun north in the spring and south in the fall, wondering what it would be like to stay in one place, have her own bed, her own bicycle. For want of time and resources, Anna is left to her imagination, a gift of childhood independent of exterior comforts. Indeed, most of the art in Migrant is the whimsical musings of a young girl making sense of a life that is by any measure, difficult.

“When her parents’ back are bent under the hot sun, when her older brothers and sisters dip and rise, dip and rise over the vegetables, that is when all of them are bees.”

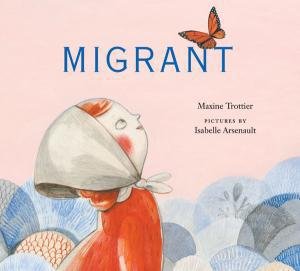

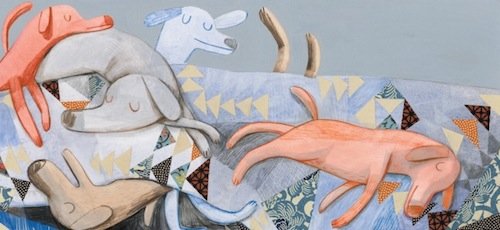

It’s a sweetly evocative image, captured beautifully by Isabelle Arsenault’s translucent watercolour, pencil, and collage illustration. In fact, the interior artwork of the book is a much richer experience than the cover of Migrant would suggest, and Arsenault’s almost child-like drawings perfectly mirror Anna’s visions, where people are quirkily bland, but the world they inhabit is a patchwork paradise of fairytale and fantasy.

Anna is at times, a jackrabbit, living in an abandoned burrow, or a kitten, snuggled up in an unfamiliar bed with her sisters. Her brothers are puppies, ‘growling and nipping in their sleep, fighting over a blanket that barely covers them all.’ Speaking only low-German (Plautdietsch) and a smattering of English, the different languages spoken around her sound like ‘a thousand crickets.’ Visuals aside, Migrant does a rare thing in children’s books of this type: it teaches without being pedantic. Nestled within the gentle artwork and exquisite wordplay is the much darker tale of migrant workers and the experience of being an outsider, even in your own country. This multi-dimensional storytelling is achieved with the lightest of touch, however, and Migrant is just as much a celebration of a young girl’s soaring imagination as it is a migrant’s story, or a Mennonite 101. Nevertheless, I did learn something.

My knowledge of Mennonite history and culture is pretty much nil. I know they are descendants of a religious sect in Germany, that the branch of Mennonites depicted in Migrant live communally and may be described as fashion-backward, unless of course you’re into kerchiefs and overalls. I know nothing in other words, and so I was surprised to discover that a group of Mennonites left Canada in the 1920’s to seek religious freedom in Mexico, only to return when their subsistence farms no longer produced enough to live.

described as fashion-backward, unless of course you’re into kerchiefs and overalls. I know nothing in other words, and so I was surprised to discover that a group of Mennonites left Canada in the 1920’s to seek religious freedom in Mexico, only to return when their subsistence farms no longer produced enough to live.

Other historical information about the Mennonites and migrant workers is included in an afterword by Trottier. Interesting coincidence: Migrant was published several months ago, as was Miriam Toew’s new novel Irma Voth (Knopf Canada). While both books refer to the Mennonite settlements in Mexico, Irma Voth does not have a single illustration of a girl riding a cricket, or any crickets as far as I know, therefore as much as I love Miriam Toews as an author, I must uphold Migrant as the Mennonite book of 2011.

Isabelle Arsenault was born in 1978 in Sept-Iles, Quebec. After studies in Fine Arts and Graphic Design, she specialized in illustration. In 2005, the Montreal-based artist won the Governor General’s Literary Award for the illustration of her first children’s book, Le Coeur de Monsieur Gauguin. Just a few days ago, Spork (Kids Can Press), a picture book illustrated by Ms Arsenault, was nominated for the prestigious Marilyn Baillie Picture Book Award.

Maxine Trottier was born in Grosse Pointe Farms, Michigan and ‘migrated’ to Windsor, Ontario in Canada with her family when she was ten years old. In 1974 she became a Canadian citizen. She is a graduate of the University of Western Ontario, and spent 30 years working as an educator in elementary classrooms. According to the book jacket, she was inspired to write Migrant after spending summers in Leamington, Ontario, where she encountered many Mennonites from Mexico. The prolific author and her husband divide their time between Port Stanley, Ontario on Lake Erie, and Newman’s Cove, Newfoundland, overlooking the Atlantic Ocean.

Migrant by Maxine Trottier, illustrations by Isabelle Arsenault. Published by Groundwood Books, 2011. ISBN: 978-0888999757

Migrant by Maxine Trottier, illustrations by Isabelle Arsenault. Published by Groundwood Books, 2011. ISBN: 978-0888999757

*Please see this article by Sherman Alexie for an eloquent response to the latest controversy surrounding YA literature.

(In my opinion) To not expose children to the darker side of life could possibly be just as damaging as to keep them in a dream world, protecting them from the sorrows of life as they grow as if they did not exist.

Perhaps we need to remember the Grimm’s Fairy Tales were just that… grim.

A balance of both, such as the character in this book using her imagination to believe in a better day, is a great virtue every child should be taught.