“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.”

It is also universally acknowledged that a single man, in want of a wife, may run afoul of a headless horseman, if he’s not careful.

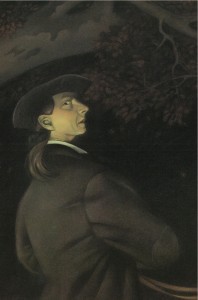

Such is the fate of Ichabod Crane, gangly bachelor and school teacher, lover of ripe repasts and an even riper Dutch damsel. A victim not only of his own appetites and superstitions, but quite possibly the terrifying prank of his rival.

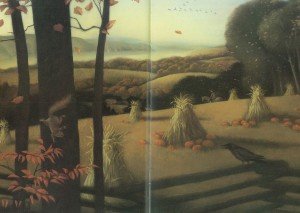

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow is an old American ghost story, based on a German fairy tale. It is familiar to many, but unread by most, due in part to the proliferation of knockoffs, cartoons and most recently, a pale cinematic adaptation by Tim Burton, starring Johnny Depp. This is a shame. In re-reading Sleepy Hollow, I was mightily impressed by the languid elegance and humour of Irving’s writing. Yes, a headless horseman, in any context, will steal the show, but equally compelling are the lush descriptions of the Hudson River Valley in Autumn, and in particular the sequestered glen known as Sleepy Hollow:

“If ever I should wish for a retreat, whither I might steal from the world and its distractions, and dream quietly away the remnant of a troubled life, I know of none more promising than this little valley.”

You see, not every ghost story is takes place in a haunted house.

Still waters run weird

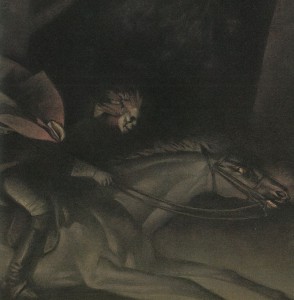

A tranquil setting lures us in, lulls the senses, so when the horror eventually unfolds, the impact is far more unsettling. Irving cleverly builds a picture of this quiet and peaceful valley, and then plants the seeds for the macabre events to follow. Sleepy Hollow is not as somnambulent as the name implies, and is, according to Irving, renowned for the peculiar character of its citizens, prone to strange visions and every manner of superstition, dominated by a belief in the ‘apparition of a figure on horseback without a head.’ This spectre is said to be a Hessian (German troopers in service with the Brits), separated from his braincase in the revolutionary war. Can’t blame the guy for wanting his head back. Every well-dressed 18th century man, dead or otherwise, wore a hat. But why all the drama?

These visual disturbances are not confined to the local inhabitants of the valley, but ‘imbibed by every one who resides there for a time.’ Enter Ichabod Crane, itinerant school teacher, ‘…esteemed by the women as a man of great erudition, for he had read several books quite through, and was a perfect master of Cotton Mather’s History of New England Witchcraft, in which, by the way, he most firmly and potently believed.” Without exception, Irving’s vivid and satirical descriptions of the locals, in particular the sorry figure of Ichabod Crane, are sublimely witty:

“The revenue arising from his school was small, and would have been scarcely sufficient to furnish him with daily bread, for he was a huge feeder, and, though lank, had the dilating powers of an anaconda.”

That, is genius.

Ichabod’s capacious appetite for all things ripe brings him to the household of a wealthy farmer, Baltus Van Tassel and most fatefully, Van Tassel’s ‘blooming’ daughter, Katrina. He is not alone in his admiration of the plump farm girl. Vying for her attention is Abraham Van Brunt, also known as Brom Bones, a heap of a man determined to win her affection. Ichabod wisely avoids any opportunity to let Bones ‘double the schoolmaster up and lay him on a shelf of his own school-house’, leaving the mischievous brute no alternative but to ‘draw upon the funds of rustic waggery in his disposition, and to play off boorish practical jokes upon his rival.’ Bully him, in other words.

The hour was as dismal as himself

Autumn descends upon the land (beautifully described by Irving), and Van Tassel lays out a banquet for the

town. As the gathering winds down, the drowsy talk turns to gossip and old war stories…and tales of the headless horseman. Brom Bones makes light of the galloping Hessian, but the story of his encounter has it’s intended effect on Ichabod, who lingers after the party disperses for a tête à-tête with the lovely Katrina. She dumps him, and the heavy-hearted Ichabod storms off into the night. ‘All the ghosts and goblins that he had heard in the evening, now came crowding upon his recollection.’ No surprise, Ichabod comes face to…well, no-face with the headless horseman:

“Just then he saw the goblin rising in his stirrups, and in the very act of hurling his head at him. Ichabod endeavored to dodge the horrible missile, but too late. It encountered his cranium with a tremendous crash.”

Ichabod’s horse is found the following day, and beside the schoolteacher’s hat, a shattered pumpkin. He is never seen again.

Brom Bones, newly married to Katrina, is ‘observed to look exceedlingly knowing whenever the story of Ichabod was related.’ Yes indeed, Mr Bones is a card-carrying 18th century arsehole. The Legend of Sleepy Hollow is about a headless horseman, but the implication is that it was Brom Bones and not the Hessian that either scared Ichabod to death, or drove him out of town. Interesting. Remember that kids, superstition kills, or at least, maims. With a gourd.

American Gothic

Gary Kelley’s pastel illustrations for this edition of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow are stunningly gorgeous, running the gamut from pastoral landscapes to full-on nightmare imagery. In the rolling hills and slightly distorted perspectives, there is a hint of Grant Wood, the mid-20th century American painter, but the darker stuff is entirely distinctive and entirely Kelley. In one of the final paintings, the dark rider is like something out of the apocalypse. His skeletal visage has no written counterpart in the text. However, this passage from an earlier German folktale by Karl Musäus (1735-1787) may be the source of Kelley’s inspiration:

“When they reached the bridge, the horseman suddenly turned into a skeleton. He threw the old man into the brook and sprang away over the treetops with a clap of thunder.”

Quite wonderful of Mr Kelley to draw from a variety of sources to fully realize the visual complexity and horror of this folktale.

As with Boshblobberbosh, the other Gary Kelley illustrated book I’ve reviewed in this blog, this oversized and exquisitely produced Creative Education publication is nothing short of a feast for the eyes. It’s a testament to the skill of Kelley’s artistry that it is able to withstand the brilliance of Washington Irving’s writing. And vice-versa.

Washington Irving (1783-1859) was America’s first internationally best-selling author. Named after the hero of the Revolution, Irving was later ‘blessed’ at the age of six by his namesake. When he was shipped off to Tarrytown New York after a yellow fever outbreak, Irving became familiar with the ghost stories of the region, particularly nearby Sleepy Hollow. The Legend of Sleepy Hollow was originally published alongside his other famous work, Rip Van Winkle (also illustrated by Gary Kelley), in a collection entitled The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon. Among his many contributions to American letters, Irving is credited with attaching the name Gotham to New York City in a satirical magazine he wrote called Salmagundi. Gotham is Anglo-Saxon for Goat City, which begs the question, why is it Batman that watches over Gotham, and not Goatman?

In reading various biographical bits about Washington Irving, I was struck by the parallels between his

life and that of Mark Twain. Both were extremely witty, satirical writers, popular at home and abroad, with early careers in journalism, and the same flair for financial vagaries and personal tragedy. Although the following quote refers to specifically to Washington Irving, it’s hard not to think of his fellow American humourist:

“Irving’s reputation soared, and for the next two years, he led an active social life in Paris and England, where he was often feted as an anomaly of literature: an upstart American who dared to write English well.”

Indeed. As mentioned, although I had read Sleepy Hollow before, for the purposes of this blog, I re-read it, and this time, I paid attention. Just as Ichabod Crane was a student of the supernatural, I think I will become a student of Washington Irving. I seem to have developed quite an appetite for this man.

Legend of Sleepy Hollow by Washington Irving (pub. 1820) Illustrations by Gary Kelley. Published by Stewart, Tabori and Chang/Creative Education, 1990

Rip Van Winkle by Washington Irving (to be reviewed.) Illustrations by Gary Kelley. Published by Creative Editions, 1993

Boshblobberbosh by Edward Lear. Illustrations by Gary Kelley. Published by Creative Editions, 1998

Wow. The Gary Kelley’s illustrations are eerie. The painting of the horse is equally dark, isn’t it? I am left in wonder -whether to feel scared of the skeleton or the horse.

[…] For a lovely edition, see this review (from the excellent blog: 32 Pages) of the 1990 version of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow illustrated by Gary Kelley. […]