You many have been wondering why, in a blog that celebrates the work of great children’s book illustrators, I have waited until now to write about Chris Van Allsburg. He is, after all, one of the most brilliant illustrators of the 20th and 21st century. An illustrator whose work, like Lisbeth Zwerger, has become synonymous with classic children’s literature. The reasons are not mysterious. I have a lot of books, including most of Chris Van Allsburg’s titles, so the queue is long. Also, while most illustrators live in obscurity, Van Allsburg is a bona fide star, thanks to the Jumanji and The Polar Express films (5 second review~get the books.) There is no particular urgency to ‘lift the veil’ on an artist whose work is well known and well loved.

Simply put, I waited until October because The Widow’s Broom is Chris Van Allsburg’s one and only Halloween book, and it is second only to The Polar Express in my esteem. And now, finally, the time has come to say a few words about a fallen witch, a flying bull-terrier, and a dose of justice delivered by a crafty old lady and an enchanted broom.

The Widow’s Broom taught me a few things about, well, brooms. They wear out. Actually, I knew that. What I didn’t know was that a witches broom not only wears out, it can also, for no particular reason, lose its power.

Perhaps a form of broom obstinence, or even broom ennui? No reason is given. In Van Allsburg’s story, a witch falls from the sky and is taken in by a lonely widow in a small village. (Hmm…can’t see how that would cause a stir.)

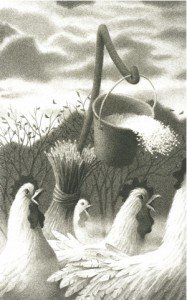

The widow Minna gives the witch a warm blanket and a bed, and in the morning she is revived. The witches broom is broken, so she leaves it behind and catches a ride with passing sorceress. Minna assumes the broom is bereft of magic, but then discovers that it still retains the ability to sweep. And sweep. And sweep. Realizing the broom’s energies might be redirected, she trains it to fetch water, feed the chickens, and play the piano. Within a short period of time, the broom and the widow have settled into a happy and useful companionship. And Mr Spivey, red-faced farmer, father, and chief alarmist of the north-east chapter of Angry Mobs Incorporated, will have none of it.

“This broom is a wicked, wicked thing. This is the devil. We’ll all be sorry if this thing stays among us.”

The opening volley takes the form of several rocks, pitched at the broom, courtesy of the Spivey brothers. When the boys start to torment the broom with sticks, the broom turns and knocks them to the ground. Chris Van Allsburg’s talent for dark, iconic words and imagery is matched by his facility with humour. Most of his books feature Fritz, a bull-terrier based on his brother-in-law’s dog. Fritz sometimes appears as a toy or as an actual dog. In The Widow’s Broom, Fritz is the Spivey family dog. When he is sent on the attack, the broom launches the dog into the air. Spivey Sr. gathers the men-folk and the widow quickly acquiesces to their demands. “It sleeps here,” she says, showing them the closet. The men take the sleeping broom out the field and burn it at the stake, or actually, the handle. Life returns to normal and the Spivey dog is found high up in a spruce tree, hungry and more than a little dumbfounded, but healthy.

In fairy tales, never underestimate a witch, or an old woman.

Or the gullibility of the ignorant. After a few days have passed, Minna calls on her neighbours with disturbing news. She’s spotted the ghost of the broom wandering through the woods, carrying an axe. At first, Mr Spivey does

not believe the old woman, until he sees the broom’s white ghost circling his house. Night after night it returns, tapping the axe lightly on the Spivey’s door. Terrified, Mr and Mrs Spivey pack up their possessions and their eight children and leave. To his credit, Mr Spivey tries to convince the widow to come with them, but she declines. Later that night, Minna is awoken by a tune being played one note at a time on the piano. “You play so nicely,” she tells the broom, still covered in the coat of white paint she’d given it. The broom bows, puts a log on the fire and this wickedly clever tale comes to a close.

The production of The Widow’s Broom is exceptional. The graphite drawings of everything from a forest of dark spruce trees to a flock of frightened chickens are so exquisitely rendered, and reproduced, the pages seem like individual prints, or even originals. There is an irresistable tactility to the ‘pencil’ art in The Widow’s Broom, and yet, I’m almost afraid to touch the illustrations lest a finger smudge the image. According to the Houghton Mifflin website, the drawings’ unusual texture was created by using a very dark litho pencil on coquille board, whose surface contains minute, pebble-like stipples that are clearly visible in the illustrations. The most stunning drawing in the book is the witch. Like a sculpture, bathed in the dark light of a haunted wood, she is a powerful, unknowable presence on the page. It’s quite breathtaking. The piano-playing, axe-wielding broom packs less of a visual punch, but Van Allsburg somehow manages to imbue the broom with a loyalty and an industriousness so endearing, Harry Potter himself would sell his left Quaffle to possess the thing.

Sometimes a pencil is not a pencil.

Not surprisingly, Chris Van Allsburg was, and still is, a sculptor. This background is particularly evident in his ‘pencil’ illustrations, such as those found in The Widow’s Broom and The Mysteries of Harris Burdick. The drawings have a visual heft, and a fantastically seemless and yet visually complex composition. Michelangelo said, “Carving is easy, you just go down to the skin and stop”. One gets the impression that Van Allsburg approaches the page in the same way. He uncovers the images, sweeping away the extraneous material until the original vision is exposed. This explanation is the only way the absolute perfection of his illustrations make any sense.

Chris Van Allsburg grew up in Grand Rapids, Michigan. He loved drawing a child, although recalls, “certain peer pressures encouraging little fingers to learn how to hold a football instead of a crayon.” He has an advanced degree in sculpture from the Rhode Island School of Design. Working full-time as a sculptor, Van Allsburg was encouraged by David Macauley to try his hand at football, I mean, picture books, and within a few years, Van Allsburg went on to win two Caldecott Medals for Jumanji and The Polar Express, a book I will be discussing in December.

I encourage you to visit the Chris Van Allsburg website. Turns out his sculptures as just as strange and beautiful as his illustrations. Talk about an embarrassment of riches! Chris Van Allsburg must have been a very, very good person in a previous life.

The Widow’s Broom by Chris Van Allsburg, published by Houghton Mifflin, 1992

The Polar Express (to be reviewed) by Chris Van Allsburg, published by Houghton Mifflin, 1985

The Mysteries of Harris Burdick, by Chris Van Allsburg, published by Houghton Mifflin, 1984