For many reasons, most of them involving packing tape, it’s been almost a month since I’ve reviewed a book in this blog. It’s become quite apparent that my brain cells must be somewhat settled before the words can flow. Not the opinions, which spew out of my mouthparts in spite of, and because of the stresses afflicting my grey matter, but writing a simple ‘I love this book’, however exuberantly expressed, just doesn’t fly in the cutthroat world of children’s picture book blogging. Nevertheless, I love Coppernickel, The Invention and I knew that once my discombobulated neurons got sorted and the packing tape put away, I would be in a position to expand on this premise. Turns out, all I needed was a blank sheet of paper.

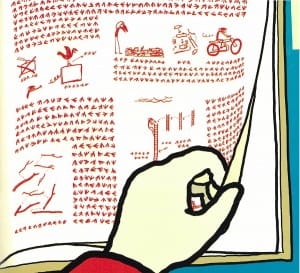

Coppernickel, a studious bird in a red hoodie, finds himself in possession of a book of ‘all the inventions ever made.’ His canine friend Tungsten wants to go outside and play but Coppernickel is too distracted by this unusual book to accommodate the dog…especially the last, blank page~

“That means there’s still room for something new to be invented.”

Excited by the possibilities, he tapes a blank sheet of paper to the wall and invites Tungsten to help him come up with ideas, the first of which is a machine for picking high-hanging elderberries. Before the dog has put pencil to paper, Coppernickel’s specs for the berry-picker and it’s many accessories have migrated off the paper and onto the wall. Tungsten accidentally pushes the knob for the ‘elderberry-detector device’ which Coppernickel has carelessly scrawled on the dog’s paper, and the Rube Goldberg-inspired machine begins to turn.

The next two pages storyboard the machine’s attempt to grip, pick, and squash Coppernickel like a high-hanging elderberry. In a scene reminiscent of Charlie Chaplin’s journey through the cogs of a machine in Modern Times, Coppernickel gets caught in a web of pulleys and thingamajigs before it spits him out.

“Maybe the elderberry-detector device needed to be adjusted.”

Uh huh. Coppernickel literally pulls his scribbles off the wall, and like all first attempts at greatness, crumples them into a ball behind his back, a particularly clever illustration by Wouter van Reek, the Dutch creator of this book and it’s accompanying TV series. Coppernickel then questions Tungsten’s drawing of a stick with a V-shape at the end. “I just don’t know exactly what it’s for.” What else? Picking high-hanging elderberries! And so they end up playing outside anyway. Clever doggie.

What is striking about Coppernickel is the contrast between the simple and the complex. The characters are drawn with thick outlines and simplified shapes, but the chicken-scratch hieroglyphics of Coppernickel’s book, some of the background elements like the trees and the storyboards, and especially his berry-picking machine are comparatively detailed illustrations. In fact, the entire book mimics the imagination of child, which is capable of extraordinary leaps of logic, and at the same time fluid enough to cut through the superfluous details of a concept and in effect, bring simplicity to the table…or the stick to the high-hanging elderberries. Tungsten’s invention is as uncomplicated as Coppernickel’s machine is complex, and yet both have the capablity of accomplishing the task, although I would in all cases recommend the stick. Much less chance of high-hanging elderberry picking injuries. As Coppernickel clearly illustrates, there is room for humour, imagination, and reason in every situation.

Although I tend to review books based on my own literary and illustrative criteria with nary a child in sight (other than my own indifferent teenage nieces and equally indifferent cat), Coppernickel is unquestionably an inspirational launching point for children who wish to create their own inventions. What haven’t we thought of yet? What do you wish existed? How do we draw it simply, and how do we draw it fantastically? What about the low-hanging elderberries? The possibilities are endless. One note: if your kid is more of a Coppernickel than a Tungsten, I would suggest a really big piece of paper.

As a child, Wouter van Reek tried to make a telescope by grinding the headlight of a scooter, but the result was that the headlight became opaque, and dreams of a science career were discarded in favour of art school. In a related story, I once tried to hatch store-bought eggs on the register. Yet another science career dashed. Thank god for art schools.

Coppernickel, or Keepvogel as it is known in Holland, was born out of an animated series for Dutch television created by Wouter van Reek.

Coppernickel, The Invention by Wouter van Reek, published by Enchanted Lion Books, 2008

We LOVE love love this book at home! (we have it in English rather than Dutch). The kids draw amazing “machines” inspired by the illustrations.

I think it’s really important to point out to children that although they just came to be in the world, it certainly hasn’t always been this way, and certainly always won’t continue to be. Why not get them dreaming now of inventions that they feel they could make come true before someone in the real world tells them differently?