It is my intention to celebrate the work of beautiful picture books in this blog. This has been to the exclusion of unpictured children’s books, which occupy far less space on my shelves but are otherwise highly valued and upstanding members of my collection. When I was a children’s bookseller, I read a lot of novels and YA, and although I continue to read and collect picture books, my attention to unpictured books has languished. Let me clarify this point: last year I was coerced into reading a popular teen vampire novel, part of a series…can’t think of the name…which my teenage nieces were raving about. I dutifully finished the book, felt a fluttering of breathless youth (quickly staunched by middle-aged cynicism), followed by a few days of fitful ennui about an entire category of books I’m no longer reading, or advocating.

It’s a shame, really. In the decade I worked at the bookstore, I read more children’s novels than I ever did as a kid, and a few of those are among the best to ever cross my book-strewn path. So, in spite of the fact that novels tend to exceed 32 pages, and are short on illustrations, I will periodically post a review of a well-loved novel in my collection, or perhaps, even a new book, if one should catch my attention.

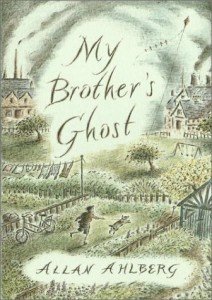

To that end, when my thoughts wander to my favourite children’s stories, I often think of My Brother’s Ghost, by Allan Ahlberg, a deeply moving, palm-sized novel set in working-class 1950’s England. Published a scant 10 years ago, My Brother’s Ghost has the feel of an old classic. An old British classic, along the same vein as Goodnight Mister Tom, by Michelle Magorian, or Nesbit’s The Railway Children. Quintessentially British, but on the sombre side of the Thames. No ‘pip pip cheerio’ or Blytonesque jolly good adventures in Ahlberg’s story, just illness, abuse and death. Hey! Come back! It’s a great book. I promise.

My Brother’s Ghost is a novel, but it reads like short autobiographical piece, recounted by Frances Fogarty, who simply and unsentimentally recalls the death of her brother when she was nine. Tom, aged 10 is struck by a milk truck. “My brother, my clever understanding older brother. My best friend and biggest pest of course sometimes. The sharer of my secrets, the buffer between me and Harry. Dead.” Frances lives with her volatile Auntie Marge, her Uncle Stan, her younger brother Harry, and a dog named Rufus. Her parents are both dead, the father in the Korean war and the mother giving birth to her baby brother. Wait. It gets worse. Frances had a bout of polio and wears a caliper. The ludicrously grim circumstances are not lost on the narrator, who interrupts her story at one point to say that she had considered excluding the part about the gimp leg, and ‘write herself a pair of normal legs’, because it’s ‘simply too much’, but opts for honesty over gloss, a philosophy shared by the author.

Soon after the funeral, Tom shows up, as a ghost, and only Frances and her younger brother can see him. Not even Tom’s dog is aware of his presence, which flies in the face of everything I think I know about dogs: “dim unseeing Rufus, no sixth sense (hardly five), went bounding through him.” Tom is able to communicate, but initially it’s a “slow growling sound, like something played at the wrong speed.” This, and other unsettling descriptions in an otherwise starkly realistic novel gives My Brother’s Ghost a kind of fairy tale resonance. Ahlberg’s powerful, evocative words keep us reading, even though we are disturbed.

Tom moves in and out of their lives for several years, both ‘here and elsewhere”, and while his benign presence becomes matter of fact to the children, it is not without a sense of bewildered observation:

“He was so like his previous self, but then…the rasp and graininess of his new voice, the almost imperceptible peculiarities in his appearance. No motion, no wind in his unruly hair, no rain on his face, only that curious shimmering, shivering at the edges of him when he ran.”

As the years progress, the children sense Tom’s loneliness, but are helpless to do anything about it. Marooned at the age of ten, while his younger siblings grow older and taller, Tom is able to intervene in their lives as a kind of guardian angel, saving their hides, literally and figuratively on several occasions, but Tom is essentially alone in his world.

Until…

Rufus dies. Tom leads him away, and neither the boy nor the dog are seen again. Heavy stuff, yes, but My Brother’s Ghost is a true gem, of the hardest but brightest design, and destined to be a classic. The appearance of a ghost is recounted not as a means to terrify, or to cause grief, but as an emblem of things, sometimes inexplicable things, that imprint on our brains not only as memories, but as feelings. I think if I had read My Brother’s Ghost as a kid, it would have stayed with me through the years, like The Railway Children, and certain episodes of Night Gallery involving dolls and brooches. Even as an adult, I think of this book often, as if maybe, it’s my own muddled memory of something that took place a long time ago, and not just a book I read.

“You won’t, I don’t suppose, believe in ghosts. That can’t be helped. The truth is, in a curious way, I’m not sure I do either. Ghosts? I cannot speak for ghosts in general. No…just the one.”

I believe. I believe.

Allan Ahlberg is one of England’s most famous and prolific children’s writers. He is the author of perennial favourites Each Peach Pear Plum, Peepo, The Jolly Postman, The Jolly Christmas Postman, and many, many others. Much of his early work was written in collaboration with his wife, Janet Ahlberg, an illustrator, who died in 1994. If the dark(ish) subject matter hasn’t scared you away, I highly recommend the follow-up to My Brother’s Ghost, another delightfully pocket-sized faux fairytale, The Improbable Cat. Needless to say, the cat ain’t right.

The beautiful cover (front and back) illustrations are by Gillian Tyler. As with many books, the cover drew me to this book, and contrary to the cliche, you can judge this book by it’s cover.

Interesting interview in The Guardian, where Mr Ahlberg discusses his career, his collaboration with his wife (and illustrator) Janet Ahlberg, and his bereavement following her death.

My Brother’s Ghost by Allan Ahlberg. Illustration by Gill Tyler. Published by Viking, 2000

The Improbable Cat by Allan Ahlberg. Illustrated by Peter Bailey. Published by Puffin Books, 2002